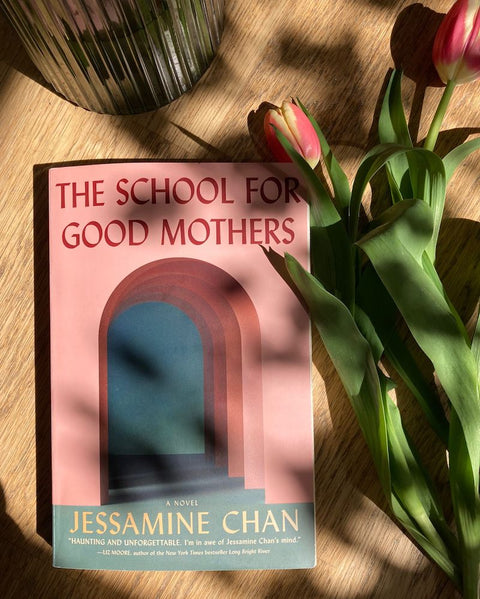

This story begins with a phone call. Frida Liu is having a very bad day with a cascade of things going wrong. Frida has a 1.5 year-old daughter named Harriet, whom she is co-parenting with her ex-husband Gust, who left Frida for the younger woman he was having an affair with. On her very bad day, Frida unwisely decides to leave Harriet home alone while she goes to retrieve a document from her office. What should have been a quick trip turns into a few hours: when Frida returns, social services have already taken Harriet. "We have your daughter," they tell her in a voicemail. And this is where the nightmare begins.

In Jessamine Chan’s debut novel The School for Good Mothers, we follow Frida as she attends a new Big-Brother-like government institution designed to teach "failed" parents how to correctly care for their children. While Harriet stays with her father Gust and her stepmother Susanna, Frida spends an entire year learning the right length for a hug, how to speak "motherese", how to diffuse a tantrum in ten minutes or less, and many other impossible tasks. All the mothers at the school are being scrutinized by childless women in pink labcoats, who set the bar of motherhood at perfection, and nothing less than perfection. If they achieve this, they get back custody of their kids.

The perfect parent does not exist

The novel gets its eerie, surveillance-state touch from the lifelike robot children that the mothers are learning with. Each mother is assigned a doll that they have to raise correctly, all while the doll is monitoring the emotions and facial expressions of the mother through an internal camera. This is on top of the constant scrutiny by the instructors, who are stiff and cold when imparting hypocritical lessons about devotion, care and love from their pedestal of privilege.

Early on the mothers must learn how to speak to their doll-child in "motherese", the "delightful high-pitched patter that goes on all day between mother and child." The mothers must achieve the right pitch and incorporate the right vocabulary. "The mothers must narrate everything, impart wisdom, give their undivided attention, maintain eye contact at all times." When they learn how to soothe a child after an injury or a tantrum, the mother must do so in ten minutes. Anything longer than that is not good enough.

All the lessons are dry and one-size-fits-all. Affection is calculated and boiled down to a formula. What they are not factoring in (or trying to remove) at this school is the unpredictability and spontaneity of humans, both children and adults. There is no standard way of acting or reacting, just like there is no standard to parenting. Emotions cannot be programmed, but that is what this school is trying to teach: that there is only one way of being a mother, and if you don’t do it that way, then you won’t ever be enough.

The double-standard of parenting

What’s even more infuriating is that the "bad fathers" at the dad’s school down the road do not experience the same conditions as the mothers do. The impossible standards and strict rules that the mothers must abide by don’t seem to apply to the fathers, who go through the rehabilitation process with limited anxiety and full confidence that they will win back custody of their children after they graduate from this school.

The unwavering bond between mother and child

Throughout Frida’s time at the school, her daugher Harriet’s presence is constantly felt, a presence that is unshakable and all-consuming, even for the reader. Caring for her doll and not for her real daughter, who is far away and to whom she hasn’t spoken to in months, feels like a betrayal of the highest order. Frida can only think of Harriet, wonders what she is doing, how she is feeling, worries for her future that hasn’t been shaped yet.

This emotion feels relatable, even to readers who do not have children. Though we might not understand the specifics of that bond, we do identify with the agony that Frida feels as a consequence of her intense love. As the reader we want to jump into the story and come to Frida’s defense, to stand up against the absurd rules of the social workers, to scream together in despair, and to try and help her get through this ordeal so that she can be reunited with her daughter.

A nightmare just short of Kafkaesque

The School for Good Mothers comes close to a dark satire of government institutions that set up people, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, to fail. Jessamine Chan mentions in an interview with her publisher that the distanced, detached narrative voice of the book was intentional. The "clinical language" and "dark, deadpan humor", "guided her from the start." This type of voice, coupled with the surreal subject matter, is reminiscent of Franz Kafka’s work The Trial. It appears as if Chan was trying to create a nightmarish government body in the Kafkaesque tradition, a world where the protagonist is constantly running in circles, encountering paradox after paradox, with no way of winning, even if they are in the right.

However, Chan doesn’t quite master this style. The detached voice clashes heavily with the intimate relationship we have with the characters, especially with Frida. The reader receives a deep look into Frida’s emotional state. We know all of her thoughts. Kafka didn’t allow us that kind of intimacy with his characters, and yet we root for them anyway.

A consequence of this stylistic choice is that the pacing is off in some parts of the book. There are a lot of terrible things that happen to Frida and the other mothers around her that sometimes get written off in a quick paragraph. They’re not given the proper time to breathe, which makes the reader care less about the characters and what happens to them. Luckily this only occurs in the last few chapters. The intensity of the buildup remains intact.

Final thoughts

One of the most important lessons we can draw from The School for Good Mothers is that humans are not perfect, and that they never will be. Perfection is a lie and cannot be attained, no matter how intensely you chase it. Love between a parent and a child is not something that can be fine-tuned with a switch. It’s intuition, experience and emotion that shapes who we are and how we interact with those closest to us.

Where to buy: The School for Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan was published in 2022 by Simon & Schuster.